A Year in Review: Eleanor Yu on Memory, the Pandemic and Creative Suffering

By Mia Hammett

Art and Film and Media Studies double major Eleanor Yu is a third-year student with all the cool, calm, and collectedness of a seasoned artist.

She’s driven to create by an equally acute attention and appreciation for the subtleties of modern life; she’s a passionate, well-articulated individual with a penchant for the abstract and experimental.

Yu’s work evokes a sense of fuzzy, out-of-focus nostalgia, as if captured through the distorted lens of time and memory. In fact, a large part of Yu’s artwork is psychological, often driven by heavy emotional or sentimental reflection.

Aside from a double major in Art and Film and Media Studies, Yu serves as an exhibition curator for the Catalyst Undergraduate Arts Gallery (Catalyst) here at UCI––a collective of undergraduate art majors working to maintain a space that fosters the creative and intellectual growth of their peers. The Catalyst’s immersive, experimentalist approach to art exhibitions functions as a jumping-off point for Yu’s own artistic tendencies, her work a series of abstracted interpretations of emotion, connection––variables of the human condition.

Truth be told, Yu finds herself destined to create. “I think it’s more of like, art choosing me,” she said. When asked about her motivation behind pursuing art, Yu is visibly overcome with a strong sense of purpose to her work. “I think art is just a thing I have to do. It was always a way to express myself… I see myself as an observer to the world surrounding me.”

I think art is just a thing I have to do. It was always a way to express myself… I see myself as an observer to the world surrounding me.

For Yu, art is a way of life; if she’s not creating, she’s not living. “I think it’s an attitude. [Art] comes to me as a quite natural thing. I want to do it properly. I think if I'm not doing it, I feel like there’s a part of me that’s like silenced. I'm muting myself, basically.”

When asked about how the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has affected her capacity to produce art, Yu recalls the obstacles she faced as an Arts student just beginning to find her footing as a double major. “I chose to double major exactly during the pandemic. I spent one year without any access to any studio, any in-person class. But I'm still doing art.”

Nevertheless, Yu carries on. “I started to realize that art is such a tool that I can use to distract myself,” she laughed, “but also to reflect on the things that I'm going through.”

Yu, who built an art studio in her garage, typically works with drawings, paintings, and small sculptures––a skill she most recently developed during the pandemic––and steers clear of photography as an art form. “I don't really like photography nowadays, because I think it’s so accessible, and I think it’s too objective, and if I were to really record a thing, I probably would paint or draw or do something unrelated, though it’s not like the exact representation of the thing that is happening, but I think it’s more accurate than a picture.” Perhaps that sense of disconnect is the cost of living in the digital age.

Yu broaches an idea for an upcoming arts project. “I’m thinking about doing screen-prints and paintings based on screenshots, because we are living in such a digitalized world. I think it’s a new form of photography, you know? Screenshots. Because when I was contacting my family during the pandemic, we were doing FaceTime, so if I wanted to take a picture of them I would just screenshot them.”

Image: Yu’s work, “A Street Scene" shown in UCI’s Art History Undergraduate Association’s 2020-2021 exhibition, “Querencia.”

Yu’s work spans years across her lifetime: Reaching into her past, Yu sets forth objects of profound personal meaning in her current work––from random bits and bobs to physical photographs. “Nothing Left But Our Memories from ‘Querencia’ is actually a small assemblage sculpture that I did during the pandemic using junk I collected,” Yu said. “I remember there was a cigarette, a cleansing wipe, buttons, a very small rose flower made from ribbon that came out from one of my clothes I usually wore in high school. All those kinds of small bits. I found the most important object in this sculpture, the Polaroid photo, which is blank.”

Here, Yu took us through the creative process behind one of her exhibition pieces:

“After I went through the sixteen days of [hotel] quarantine, I still had seven days to go… I started to dig through stuff in my childhood house. I found this pile of Polaroid photos that are completely blank. I remembered that those were the photos that I took with my family when we were living in Australia.

“It really made me think about the concept of memory, because even though you have those, why do people take photos, right? People want to make the moment permanent. But they’re not permanent, we’re not permanent. The Polaroid photos, if they are exposed to sunlight, go blank. And the concept really struck me, that everything will eventually go away, even if you stay and you take photos.

“Your memory can be evocative by subtle details,” Yu pointed out. “I started to record the memories in that summer and I remember someone in my family who smokes, that’s one of the memory pieces, mementos, basically. I remember flowers there. The coins with the Queen’s head. So all these little tidbits, I'm trying to recreate them with the current junk I have.

“Memories are recorded in this kind of messy style, but it’s still so precious and so permanent. They feel even more real and authentic than the photographs that can record every single detail.”

Upon taking the photograph of the sculpture, Yu recognized an added, unintentional layer of depth to her work. “I asked my mom to hold the frame of it. I think the eventual work was the photography rather than the sculpture, because my mom becomes another very important subject matter in this photo. I asked her to hold it and cover her face because I want the viewers to feel alienated. I think my mom was the embodiment of me, somehow, in this photo. And I want [the viewers] to feel like this is a subtle gesture of denial, a little bit of melancholy, I would say.”

Art is very important, very crucial; it's a way of knowing ourselves.

Yu’s interests in art, film and media were heightened at a particularly fraught point in her academic career. “Sometimes I think in high school, I was a bit like, in the swamp of nihilism, thinking nothing was real and everything’s so deconstructed. I think maybe art was the only thing that’s real. The people around me were like, ‘art is so useless and you should go to those popular majors.’ But that’s not true. Art is very important, very crucial; it's a way of knowing ourselves.”

“When I think about drawing or painting, it’s essentially traces you leave… I think that is actually a metaphorical embodiment of life itself. Because life is just some trace you’ve left.” After all, Yu asks, “Why do we pursue anything in life? We want to leave a trace. We want to interact with a blank paper.”

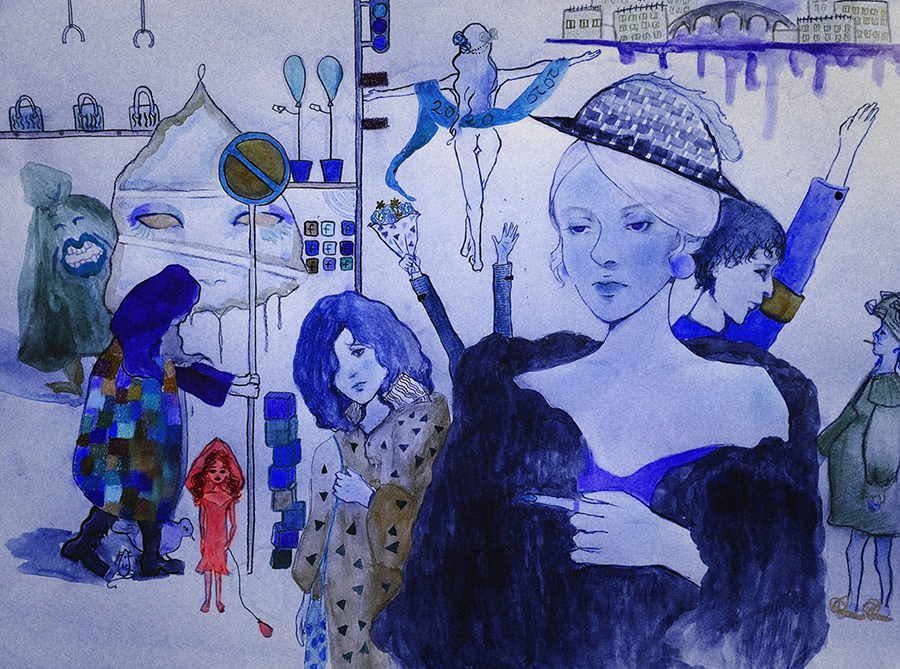

Image: Eleanor Yu, "Dear Modern Venus," 2020.

“When it comes to use of color, I really like to use blue and red––my favorite color palette. I think that's the most distinct thing about my paintings and drawings.”

When contextualizing her creative work among the work of her peers, Yu is often met with the same, trite observation. “They’ll say, ‘Your art looks kind of melancholic,’ and that’s the special thing about my art. Because I'm always exploiting things like alienation, isolation, subtle moments in contemporary life.”

For Yu, there’s an enticing, sort of requited romance in producing works of art. “The white canvases, the heavyweight papers, they are very inviting. They invite you to put marks on it. I think they are very seducing, to be honest,” she laughed. “I want to almost contain them with my brushstrokes, with my paint. And that’s always the first motivation I have. I see this blank paper and want to interact with it, leave a trace.” It’s a love affair between the painter and the painted, the sculptor and the sculpted.

As she endures the creative process, Yu finds herself embracing spontaneity. “I try to not control materials too much, recently, because I appreciate the randomness of art. Allow that randomness to flow in your work, to interact with your work; allow the mistakes.”

Such radical principles of art may very well be one of the creative forces behind Yu’s latest assemblage sculpture. Yu even has an appreciation for random, found objects––like the bits and bobs in your nightstand’s drawer, now rife with meaning. “That's why I also like found objects, like junk artworks, because I think junk has this randomness. It comes to you and you have no choice. You're living in this industrialized world; you buy the product that's produced by somebody else. With junk in the consumption of these industrial products, was also an inspiration because I think they are random as well. But you can give it new meaning.”

Why do we pursue anything in life? We want to leave a trace. We want to interact with a blank paper.

Yu points to famed artists Francisco Goya and Francis Bacon for inspiration, and cited the Los Angeles Watts Towers as a point of great artistic and architectural achievement. In Yu’s own words, the towers are a “pointless beauty; it is not functional, not high end,” but entirely authentic––and are, suffice to say, a clear inspiration behind Yu’s own assemblage work.

Yu acknowledges that she’s still in the self-discovery process as an artist––and she appreciates the wiggle room, the ebb and flow of her art style that inevitably sharpens with age and experience. “Because I’m a student artist, the key motivation of my art-making is that I try to experiment with things. I try to explore a bit. I haven't figured out my fixed style at this stage yet––I’m still trying to find the plateau.”

A consistent art style or not, there’s a relationship that emerges between the viewers and Yu’s artwork. “I think most of my artwork works on psychological movements and emotions. I want viewers to interact with my artwork. I think all the artworks are finished by the viewers. It's up to their explanation. They can have their own interpretations.” As an artist, Yu feels responsible for preserving the sanctity of one’s own reading of the work.

“I do capture something like isolation, loneliness, those kinds of things. Everybody feels it, but nobody really, seriously talks about it.” Those deep, often dark feelings present in Yu’s artwork are drawn from Yu’s own emotional turmoil––not from some manufactured or premeditated idealization of the “tortured artist.”

In fact, Yu swears against the glorification of artists’ suffering––an interpretation often present on television, in the media, or in studies of age-old creatives.

“I don't like the fact that people are romanticizing artists’ suffering,” Yu said. “Everybody suffers. Artists’ suffering are not special. We just articulate them.”

“The thing that inspired me to do artwork is not my suffering,” Yu explained. “Nowadays, the sufferings of the artist are largely romanticized. Because it's not that that made them great artists. What makes them great artists is that they survived all those things. That's why they made those great artworks, not because of the sufferings, but because of the surviving.

“Even though I say, ‘oh, the pandemic really hit me,’ it's the fact that I was supported by my friends and family that really enabled me to do art.”

Yu parts with a final truth: “Every person who’s living their life and trying their best to live life are brave people. They are brave by nature. Ordinary people are brave.”

Join us on a journey of discovery leading up to #UCIGivingDay 2022 on May 18, as we highlight current faculty and students at CTSA and learn more about what the pandemic has taught them about adaptability and innovation as we emerge brighter! Follow us on social media @ctsa_ucirvine.

Mia Hammett is a second-year English major in the School of Humanities.